Fall 2019: Help, I Can’t Move My Legs!

Abstract

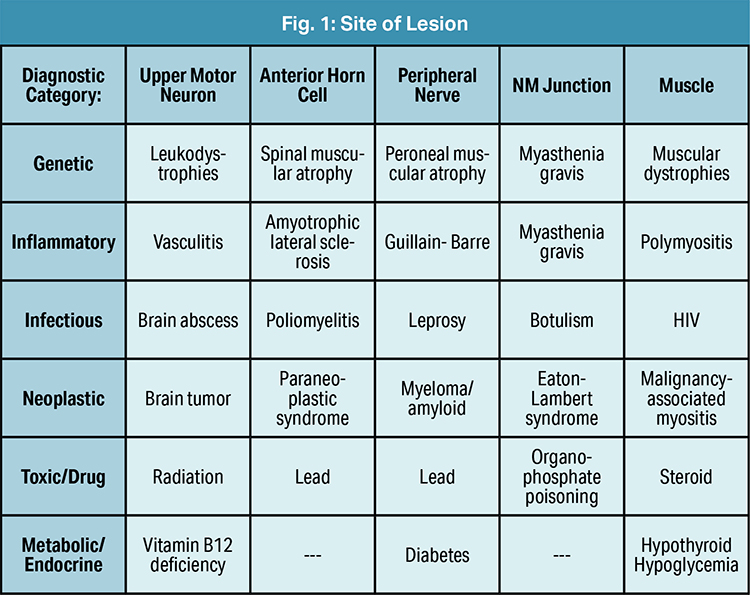

The approach to a patient complaining of weakness includes three key components: distinction of muscle weakness vs. motor impairment, localization of the site of the lesion, and determining the cause of the lesion.

In an undifferentiated patient, weakness is separated based on site of the lesion and diagnostic category (Fig. 1). The differential for weakness is broad and includes genetic, inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, toxic and metabolic causes. [1] The history and physical examination can help guide and tailor this broad differential to identify the cause of weakness in a patient.

Patient Presentation

A 27-year-old male with no significant past medical history is brought in via EMS to the Emergency Department for a month-long history of worsening bilateral lower extremity weakness. He woke up the previous night with an inability to move his lower extremities, followed by a fall after attempting to get out of bed. He eventually regained strength and was able to walk a short distance before falling again. There was no loss of consciousness nor head injury as a result of his falls. He denied recent illness, trauma, associated headache, numbness/paresthesia or facial weakness. ROS was notable for recent unintended weight loss and palpitations.

On physical exam he was afebrile, tachycardic to 111 and normotensive. Neurologic exam was notable for proximal > distal weakness in the lower extremities (2/5 at hips, 4/5 at ankles) and hyporeflexia (1+ patellar). HEENT, cardiac, pulmonary, spine and the rest of the neurologic exam was otherwise normal.

Initial work-up included complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, creatine kinase, magnesium, urinalysis, electrocardiogram and chest x-ray. His BMP was notable for potassium of 2.6 mmol/L (reference: 3.3 – 5.1 mmol/L). The rest of his workup was unremarkable. Thyroid stimulating hormone, free T4, and T3 were added after initial labs and neurology was consulted for further workup. Thyroid studies were notable for: TSH <0.030 mIU/L (reference: 0.400 – 5.000 mIU/L), free T4 3.49 ng/dL (reference: 0.60 – 1.20 ng/dL), T3 280 ng/dL (reference: 87 – 178 ng/dL), free T3 8.0 pg/ml (reference: 1.8 – 4.2 pg/ml).

His potassium was repleted and he was admitted to general medicine for further evaluation/observation. Endocrinology was consulted inpatient, and he was started on methimazole 10mg BID and propranolol 10mg TID for symptomatic management. By the next day, he had significant improvement in strength and the patient was discharged with endocrinology follow-up.

Ten days after discharge, he presented to the ED with substernal chest pain and muscle weakness. He was in sustained ventricular tachycardia, had increased work of breathing and was unable to move his distal extremities. He was given amiodarone and cardioverted twice. He converted to normal sinus rhythm on the second attempt. He had severe hypokalemia to 1.5 mmol/L (reference: 3.3 – 5.1 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia to <1 mg/dL (reference: 2.7 – 4.5 mg/dL), and hypomagnesemia to 1.7 mg/dL (reference: 1.5 – 2.8 mg/dL). He was given dexamethasone, electrolyte repletion was started, and he was admitted to the medical intensive care unit. In the ICU, his propranolol was increased and he was monitored for two days with stabilization of his electrolytes and improvement in his free T4 levels. The electrolyte imbalances were thought to be driven by the hyperthyroid state, and the cardiac arrythmia was driven secondary to the electrolyte imbalances.

The patient has been followed up extensively by endocrinology on an outpatient basis and was continued on his beta-blockers and methimazole. He is currently undergoing titration of his antithyroid medications and, per the medical record, denies any recent episodes of paralysis.

Discussion

Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis (TPP) is a rare complication of hyperthyroidism characterized by hypokalemia and muscle paralysis secondary to an intracellular shift in potassium levels. [2,3] The condition primarily affects proximal muscles more that distal muscles and involves lower extremities greater than upper extremities. [4] Symptoms of TPP can commonly be misdiagnosed for other metabolic, neurologic and idiopathic pathologies. Despite a higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females, TPP occurs predominantly in males, and while it does not have familial inheritance, key human leukocyte antigens in Asians have been associated with increased susceptibility in developing TPP. [5,6]

TPP is initially managed by careful potassium replacement therapy, nonselective beta-blockers, and addressing any underlying hyperthyroid complications. Antithyroid medications are added once the patient is stable to control the hyperthyroid symptoms. [7,8,9] ■

References

- Miller, ML (2019). Approach to the patient with muscle weakness. In M. R. Curtis (Ed.), UpToDate. Retrieved Aug. 16, 2019, from www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-muscle-weakness

- Kung AW. Clinical review: Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(7):2490-5. doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-0356

- Vijayakumar A, Ashwath G, Thimmappa D. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: clinical challenges. J Thyroid Res. 2014;2014:649502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/649502

- Meseeha M, Parsamehr B, Kissell K, Attia M. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a case study and review of the literature. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7(2):103-106.

- Lam L, Nair RJ, Tingle L. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2006;19(2):126–129. doi:10.1080/08998280.2006.11928143.

- Tamai H, Tanaka K, Komaki G, et al. HLA and thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in Japanese patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64(5):1075-8.

- Sharma ZD, Gokhale VS, Chaudhari N, Kakrani AL. Thyrotoxicosis presenting first time as hypokalemic paralysis. Thyroid Research and Practice. 2013;10(3):114. Doi: 10.4103/0973-0354.116132

- Meseeha M, Parsamehr B, Kissell K, Attia M. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a case study and review of the literature. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7(2):103-106. doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2017.1316906

- Neki NS. Hyperthyroid hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(4):1051-2. Doi: 10.12669/pjms.324.11006

Samantha manages fcep.org and publishes all content. Some articles may not be written by her. If you have questions about authorship or find an error, please email her directly.

This article originally appeared in EMpulse Fall 2019. View the

This article originally appeared in EMpulse Fall 2019. View the