POCUS of the Gallbladder: Always in Style

In my short time practicing EM, I have seen some point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications go “out of fashion.” However, similar to how Ferraris are always cool, some ultrasound scans have stood the test of time and are always “in.” For me, that classic scan is POCUS of the gallbladder.

I remember a case from early in my residency training. A 42-year-old female with a past history of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) presented to the emergency department with 12 hours of dull burning epigastric pain. She had visited the ED two times for GERD in the last two months. Each time she had normal lab tests and she was treated with a GI cocktail. She got better and went home.

On this visit, her vitals were normal and she told me the pain felt like her usual GERD pain. “I just need a GI cocktail, doc!” she said. I wasn’t convinced. I performed a POCUS of her gallbladder and found a large gallstone with sonographic signs of cholecystitis! Within six hours, she was taken to the OR for a cholecystectomy.

Acute abdominal pain accounts for 7-10% of ED visits. Pain located in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) or epigastric region should prompt the diligent emergency physician (EP) to perform a POCUS of the gallbladder.

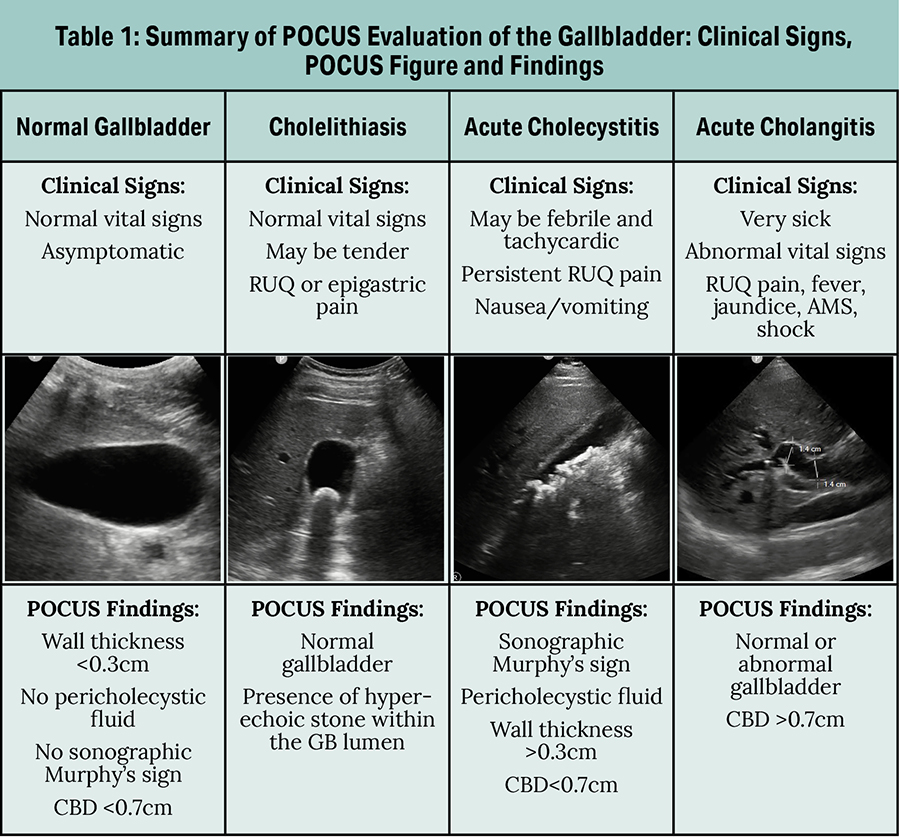

When scanning the gallbladder, the diligent EP should look for gallstones, signs of cholecystitis and signs of biliary ductal dilation. If the POCUS does not show any of these, the EP should search for causes of abdominal pain other than biliary disease.

While some may use a phased array transducer to scan the gallbladder, I prefer a curvilinear transducer. There are several techniques that one can use to find the gallbladder. The three most common approaches are: a subcostal approach (the probe is placed on the right side of the abdomen, looking up at the liver and gallbladder); a RUQ-coronal approach (the probe is placed on the flank), and an “X-7” (the probe is placed 7 cm to the right of the xiphoid process).

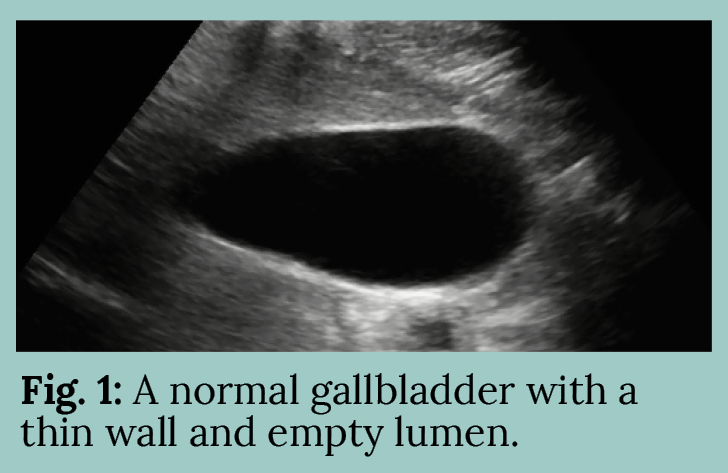

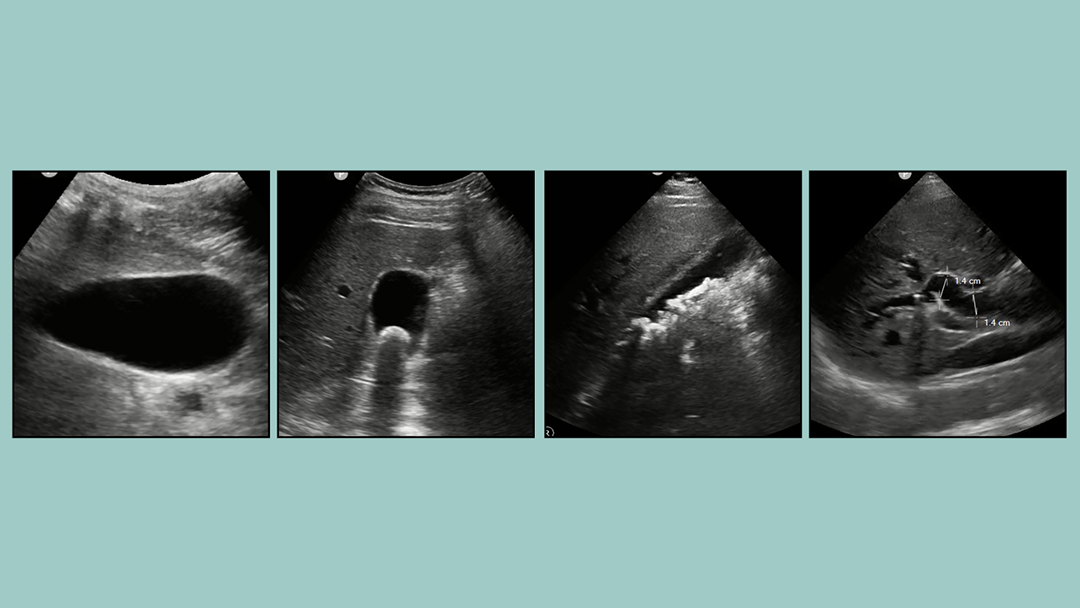

The location of the gallbladder can vary from patient to patient. If the gallbladder is difficult to find, have the patient lie in a left lateral decubitus position, or ask the patient to take a deep breath and hold it as long as possible. Both of these maneuvers will help bring out the gallbladder from under your patient’s ribcage. Once found, look for signs of a normal gallbladder, as shown in Fig. 1.

That’s one happy looking gallbladder!

Not all gallbladders are as happy. Some have stones and some are infected.

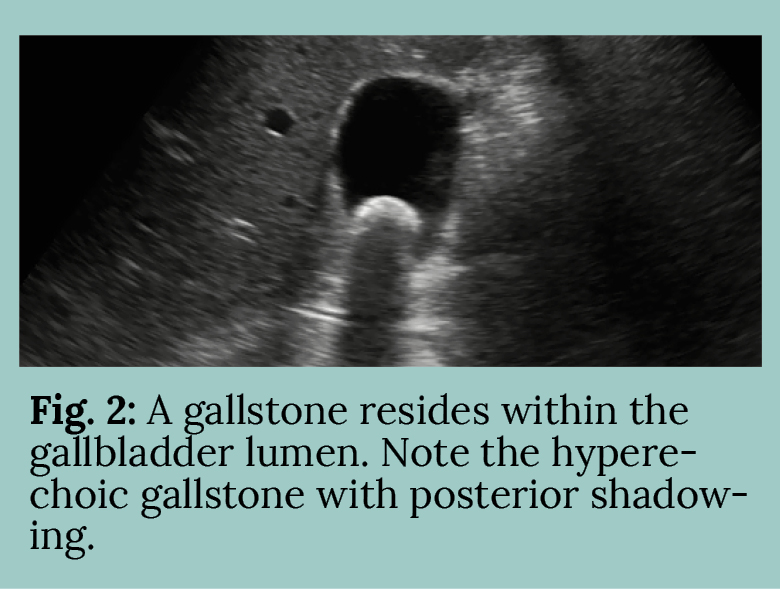

The presence of a gallstone in the gallbladder is easy to identify: a mobile hyperechoic mass with posterior anechoic shadowing. The gallstone lies in the gravity dependent portion of the gallbladder. If the gallstone is not mobile, it may be impacted, as shown in Fig. 2.

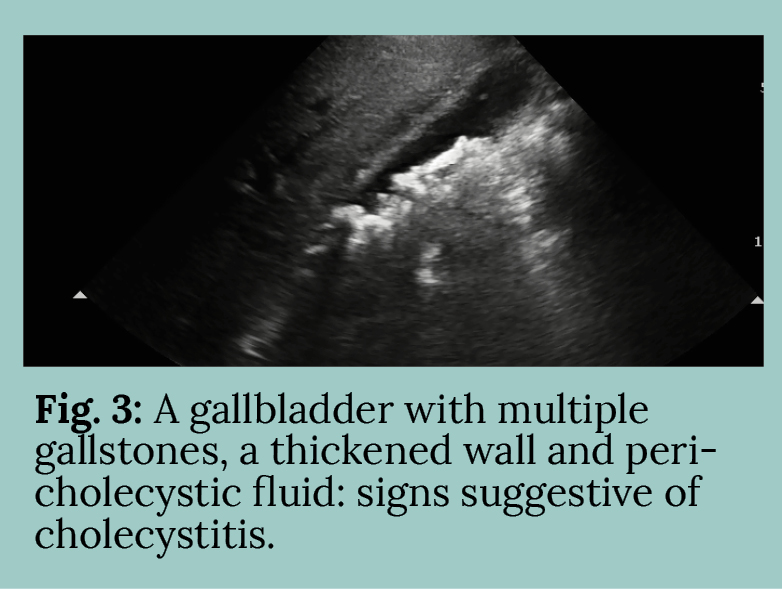

Now here’s an unhappy gallbladder in Fig. 3.

The most obvious sign would be the presence of sonographic Murphy’s sign: pain when the gallbladder is compressed underneath the ultrasound transducer. This is the most sensitive sign of acute cholecystitis. Other signs of an unhappy gallbladder include gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid, both of which we can see in Fig. 3. These signs indicate edema of the gallbladder and gallbladder fossa, secondary to inflammation often resulting from infection.

Finally, the diligent EP must evaluate the diameter of the common bile duct (CBD). Sometimes gallstones can actually get lodged in the bile duct, and this will cause a dilation of the CBD. The CBD is one of the three vessels of the portal triad, the other two being the hepatic artery and the hepatic portal vein. The CBD can be identified in the portal triad as the only vessel that will lack flow on color Doppler imaging, as bile flows much more slowly than blood. The diameter of the CBD should be measured perpendicularly from inner-wall to inner-wall, and a measurement of greater than 7 mm should increase suspicion for possible choledocholithiasis, or even cholangitis.

Even the best POCUS is less sensitive and specific for biliary disease than a cholescintigraphy, as my surgical colleagues often remind me when we pass in the hallways. Nevertheless, POCUS has a superior sensitivity, specificity and safety profile than the CT scan for evaluating biliary disease. “Ultrasound first” should be every diligent EP’s motto!

POCUS is a powerful tool to evaluate the normal gallbladder and to diagnose cholelithiasis, cholecystitis and choledocholithisasis/cholangitis. Table 1 summarizes the POCUS evaluation of the gallbladder: clinical signs, POCUS figure and findings. I make sure I perform POCUS on all my patients with RUQ or epigastric abdominal pain patients. And I have found that my surgical colleagues are thankful. ■

This article originally appeared in EMpulse Fall 2019. View the

This article originally appeared in EMpulse Fall 2019. View the