A Disappearing Act: The curious case of Lemierre’s Syndrome

Background

The textbook definition of Lemierre’s syndrome is thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. This serious condition usually follows an oropharyngeal infection with ensuing septic emboli. The syndrome usually manifests with Fusobacterium necrophorum as the causative organism. Diagnosis of this rare condition can be made by confirmation of thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein via imaging, positive culture of F. necrophorum, or demonstration of septic embolization secondary to thrombophlebitis. [1]

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old-male with questionable retropharyngeal abscess, which extended into the mediastinum, had concerning features for Lemierre’s syndrome. Diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome was confirmed by duplex ultrasound of the neck. The condition was managed with prolonged usage of intravenous antibiotics.

Conclusion

Having suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome in any patient who presents with probable retropharyngeal abscess is important as early diagnosis and treatment can lead to a complete recovery of this rare condition.

Case History

A 63-year-old Hispanic male presented to the Emergency Department as a transfer from an outside hospital who endorsed sore throat, cough, congestion, and difficulty swallowing for the past several days. He complained of severe throat pain that was aggravated by neck movements. Due to the patient having a very muffled voice, and the need to secure his airway quickly, gathering a history from the patient was difficult. Much of the history was obtained from the patient’s family. As preparations were made in the Emergency Department for a difficult airway, his O2 saturation began to decline while on room air. He began to complain of inability to swallow secretions, as well as inability to breathe while laying flat. The patient was intubated in the ED for airway protection, using awake intubation with ketamine in a seated position with a GlideScope Video Laryngoscopy device. Intubation was complicated by trismus, edematous vocal cords with a narrowed glottic opening, and pus in the airway; however, it was performed successfully in a single attempt. Prior to arrival from the outside facility, the patient had been given Vancomycin, Zosyn, and Decadron.

On physical examination, the patient was intubated and sedated. On arrival and on examination, the patient’s temperature was 37.5C. On examination, there was considerable erythema and edema over the anterior neck, which extended to the upper right arm. Examination of the oropharynx revealed poor dentition without evidence of peritonsillar abscess; the uvula was midline, and no erythema was noted in the oropharynx.

Initial laboratory analysis showed a WBC count of 2.8/mm3 with left shift and consisted of 86% neutrophils. The C-reactive protein (CRP) was abnormally elevated at 56mg/dL. Serum electrolytes revealed hyponatremia (131mmol/L), hypertriglyceridemia (301mg/dL). Urinalysis was positive for hematuria without evidence of infection. Evaluation of BUN (37mg/dL) and Creatinine (1.64mg/dL) showed an acute kidney injury. Further laboratory analysis showed lactic acidosis and transaminitis. In order to further assess if surgical intervention would be required for a deep neck abscess, CT of the neck and chest with contrast was performed. CT of the chest showed bilateral pleural effusions with underlying areas of consolidation. CT of the neck revealed a soft tissue density in the nasopharynx and oropharynx, as well as mild thickening of the prevertebral soft tissue without evidence of drainable fluid collection. At the time of CT scan of neck, no filling defect was visualized. The patient was transferred to the ICU for further management.

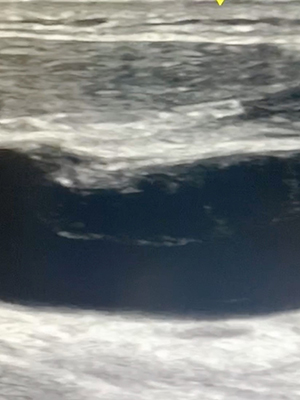

While in the ICU, there was a lingering suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome. An initial duplex of the neck was performed, which showed echogenic material within the right internal jugular (RIJ) vein; possibly representing partial, nonocclusive thrombus versus sluggish flow. The confirmation of a thrombus could not be confirmed due to absence of Doppler imaging. The next morning, an educational bedside ultrasound of the neck did, in fact, show a thrombus in the RIJ. However, later that day a second ultrasound of the neck was performed; the echogenic material seen on the prior study was no longer present, which indicated that the clot had either resolved or embolized.

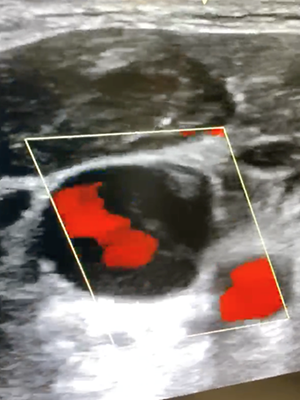

The following morning, another educational ultrasound with Doppler imaging did reveal a thrombus in a non-collapsible RIJ. A stat formal ultrasound with Doppler imaging of the neck was quickly performed, which showed a deep venous nonocclusive thrombus involving the RIJ as well as a superficial thrombophlebitis in the right cephalic vein. These ultrasound findings confirmed our diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome. [2] A repeat CT of the chest was performed given concern for embolization from the RIJ. CT chest revealed improved pulmonary edema with decreased pleural effusions and did not show any evidence of embolization to the lungs, however it did show new right middle lobe opacity, suggesting pneumonia.

Fig. 1: Longitudinal view of right internal jugular vein with visible thrombus formation

Fig. 2: Color flow sagittal view of right internal jugular vein exhibiting thrombus formation

Treatment

The blood cultures that were performed did not show any growth. After confirmation of Lemierre’s syndrome, the patient was kept on intravenous Zosyn (3.375gm q12hrs) and Zyvox (600mg q12hrs). Anticoagulation therapy with Heparin (5000U q8hrs delivered subcutaneously) was also started on the patient. Throughout the course of stay in the ICU, the patient’s condition gradually improved with significant reduction in erythema and edema of the anterior neck. The patient underwent a bronchoscopy and was extubated without problem.

Discussion

Prior to the advent of antibiotics, the incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome was at its highest. This incidence met a sharp decline once penicillin entered the scene. However after the 1970s, there has been a rise in the reported case of Lemierre’s syndrome. This may be attributed to the steady dwindling use of empiric antibiotics to treat oropharyngeal infections. With this said, the worldwide incidence of this rare disease is approximately 1/1,000,000. The syndrome typically targets previously healthy young adults and adolescents. Approximately 90% of patients who come down with Lemierre’s syndrome are between 10 and 35 years of age. [3, 4]

The diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome is mainly clinical and should be considered in patients with oropharyngeal infection who begin to develop respiratory symptoms, neck swelling, or evidence of toxicity about a week after oropharyngeal infection symptom onset.5 In patients with the clinical presentation of oropharyngeal infection with associated soft tissue neck swelling, a broad differential must be considered. Such differentials include retropharyngeal abscess, infectious mononucleosis, Ludwig’s angina, and peritonsillar abscess. Imaging modalities to help diagnose Lemierre’s syndrome typically include CT imaging of the neck and chest, as well as color doppler imaging in order to visualize thrombosis and potential pulmonary emboli as a sequelae of thrombosis. [6]

Antibiotic coverage should include oral anaerobes. Duration of treatment is variable, however patients should be treated with IV antibiotics for 2-3 weeks until clinical improvement is observed. This should be piggybacked with a 4-6 week period of oral antibiotics. [7]

Conclusion

In any patient who presents with a deep space tissue infection of the neck following an oropharyngeal infection, clinical suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome should be high. Lemierre’s syndrome is a potentially fatal condition that is characterized by septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to oropharyngeal infection with potential embolization to the lungs as well as other organs. Given the correct clinical setting, diagnosis can be made via CT, MRI, or ultrasound of the neck indicating internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis. ■

References

- Katrine M Johannesen, U. B. Lemierre’s syndrome: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Infect. Drug Resist. 9, 221 (2016).

- Nadir, N.-A., Stone, M. B. & Chao, J. Diagnosis of Lemierre’s Syndrome by Bedside Sonography. Academic Emergency Medicine vol. 17 E9–E10 (2010).

- Allen, B. W. & Bentley, T. P. Lemierre Syndrome. in StatPearls [Internet] (StatPearls Publishing, 2019).

- Sacco, C. et al. Lemierre Syndrome: Clinical Update and Protocol for a Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Hamostaseologie 39, 76–86 (2019).

- Kristensen, L. H. & Prag, J. Human Necrobacillosis, with Emphasis on Lemierre’s Syndrome. Clinical Infectious Diseases vol. 31 524–532 (2000).

- Riordan, T. Lemierre’s syndrome: more than a historical curiosa. Postgraduate Medical Journal vol. 80 328–334 (2004).

- Riordan, T. Human Infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a Focus on Lemierre’s Syndrome. Clinical Microbiology Reviews vol. 20 622–659 (2007).

- Li, H.-Y., Grubb, M., Panda, M. & Jones, R. A Sore Throat—Potentially Life-Threatening? Journal of General Internal Medicine vol. 24 872–875 (2009).

- Karkos, P. D. et al. Lemierre’s syndrome: A systematic review. The Laryngoscope vol. 119 1552–1559 (2009).

This article is part of the following sections:

Samantha manages fcep.org and publishes all content. Some articles may not be written by her. If you have questions about authorship or find an error, please email her directly.