An unrecognized opportunity to diagnose Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and decrease transmission in people who inject drugs (PWID)

Abstract

This is a case of a 47-year-old patient who injects drugs (PWID) that presented to the emergency department (ED) with a right arm cellulitis and was diagnosed with acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) seroconversion. The patient presented during a window phase with a negative HCV Ab but detectable HCV RNA PCR. Identification of patients with HCV in PWID decreases viral transmission and provides opportunities for linkage to care, leading to improved rates of sustained virologic response (SVR)[1]. The HCV screening algorithm [2] may not capture all opportunities for diagnosis in high pretest probability PWID patients during ED encounters. In patients at high risk for acute seroconversion (testing prior to time to mount antibody response), an under-recognized window phase may lead to a false negative classification of HCV status. Thus, when testing high pretest probability patients for HCV, providers should consider ordering a HCV RNA even if the HCV Ab is nonreactive. Routine screening for HCV did not identify the infection because the patient had not yet seroconverted. Studies have shown [3,4,5] that ordering an HCV RNA PCR may uncover previously unidentified HCV infections in PWID. Earlier detection of HCV status in patients during acute seroconversion may lead to decreased transmission of HCV in needle sharing networks, as well as improved chances of linkage to care for treatment and increases chances of obtaining SVR by 26%. [6]

Introduction

Persons who inject drugs (PWID) represent most people with hepatitis C virus(HCV), as intravenous drug use (IVDU) has become the primary route of HCV transmission.[1,7] Identification of patients with HCV decreases transmission throughout PWID needle sharing networks and provides opportunities for linkage to care and treatment that can lead to sustained virologic response (SVR) through the use of direct acting antivirals (DAA) which are 95% effective even among PWID.8 The HCV screening algorithm, which does include the emergency department (ED) as a potential place for HCV screening,[2] may not capture all opportunities for diagnosis in high pretest probability PWID patients during ED encounters. In addition, PWID are higher utilizers of the ED compared to non-PWID,[9] presenting an opportunity for HCV testing that may alter the epidemiology of comorbid disease (HCV and injection and drug use) through early detection. Early detection may lead to decreased needle sharing related HCV transmission and improve the rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) through linkage to care and DAA initiation.Narrative

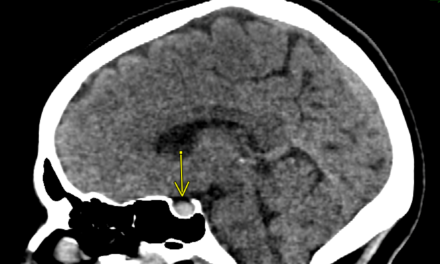

A 47-year-old man with a history of intravenous drug use (IVDU) presented to the ED with a 1cm puncture wound surrounded by 3cm of erythema and induration on the right forearm (Figure 1). Initial vital signs in the ED were unremarkable and remained stable during the ED course. Following CDC guidelines,[2] routine screening for HCV was completed during the ED encounter, and the HCV Ab was non-reactive.

Figure 1. Right forearm puncture wound and surrounding erythema

A complete metabolic panel (CMP) was also obtained and demonstrated an AST of 393 U/L (5 – 34 U/L) and an ALT of 324 U/L (5 – 55 U/L). The patient was diagnosed with a right forearm cellulitis. As part of a laboratory panel to test for hepatitis A and hepatitis B, the HCV Ab immunoassay was repeated. All of these antibody immunoassays were non-reactive. However, given the high pretest probability for acute seroconversion of hepatitis C in the context of IVDU with transaminitis, an HCV RNA PCR was ordered to test for the presence of quantifiable virus. The patient was admitted secondary to several other concomitant metabolic abnormalities, including acute kidney injury and hyponatremia, providing an opportunity to follow the HCV RNA PCR results during the hospital course. Typically, an HCV RNA PCR is only obtained in the setting of a reactive HCV Ab.[2] The HCV RNA PCR identified 111,677 copies of the virus. On a subsequent ED encounter two months later, the patient was found to then have a reactive HCV Ab and 10,502,710 copies of HCV detectable via RNA PCR. HBV Ab was also reactive on the subsequent encounter and 31,946 copies of HBV were identified.Discussion

A patient with known IVDU presented to the ED during the acute seroconversion phase of a newly acquired HCV infection. Routine screening and a hepatitis panel failed to detect the HCV antibody, while a PCR test did quantify a detectable level of HCV RNA. The patient presented during a window phase in which HCV RNA was detectable, but the HCV Ab was still non-reactive. The current CDC HCV algorithm is a screening algorithm.[2] ED patients may present with higher pretest probability for disease. HCV RNA testing in PWID leads to earlier detection, status notification, linkage to care and subsequent SVR, as well as decreased HCV transmission in needle sharing networks. In a cohort of 32 people, one PWID with chronic HCV transmitted the virus to 30 additional users in the same social group within a span of six months,[10] and chances of contracting HCV per needle sharing event are roughly 57%. This case represents a patient with HCV that could have been missed due to presentation during the window of seroconversion, suggesting that providers should consider ordering an HCV RNA by PCR if the patient is being tested for HCV with high pretest probability for disease (e.g., PWID). Test turnaround time (TAT) for the HCV viral load represents a current barrier of clinical implementation of this strategy as many facilities cannot return an HCV RNA result during the ED encounter. Thus, the result may become available during hospitalization, or short-term follow up should be arranged for further PCR testing (if the HCV Ab is non-reactive and the patient has high pretest probability for HCV, but HCV RNA is not ordered in the ED) or to receive test results (if HCV RNA PCR is ordered in the ED, but not available during clinical encounter). In the future, an ability to detect HCV RNA in a serum sample during an ED encounter (e.g., rapid point-of-care viral load testing) may facilitate wider adoption of an important strategy as HCV prevalence will continue to increase during the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States.

References

- Shiffman ML, Gunn NT. Impact of hepatitis C virus therapy on metabolism and public health. Liver Int. 2017. doi:10.1111/liv.13282

- Testing for HCV Infection: An update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR 2013; 62. Early Release.

- Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, Garazzino S, De Rosa FG. Treatment of acute C hepatitis in intravenous drug users. J Hepatol. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.010

- Judd A, Hickman M, Jones S, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C virus and HIV among new injecting drug users in London: prospective cohort study. Br MeD J. 2005; doi:10.7748/phc.16.2.8.s10

- Edlin, Brian R et al. Managing Hepatitis C in Users of Illicit Drugs. Curr Hepat Rep. 2007. doi:10.1007/s11901-007-0005-8

- Calner, Paul et al. HCV screening, linkage to care, and treatment patterns at different sites across one academic medical center. PloS one. 2019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218388

- Harder, J., Walter, E., Riecken, B., Ihling, C., Bauer, T. 2004. Hepatitis C virus infection in intravenous drug users. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1469- 0691.2004.00934.x

- Grebely, J., Dalgard, O., Conway, B., Cunningham, E., Bruggmann, P., Hajarizadeh, B. 2018. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1

- Fairbairn N, Milloy MJ, Zhang R, et al. Emergency department utilization among a cohort of HIV-positive injecting drug users in a Canadian setting. J Emerg Med. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.020

- Henderson, H. 2018. “I am More Than my Addiction”: Perceptions of Stigma and Access to Care in Acute Opioid Crisis. (Master’s Thesis). University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I database. (UMI No. 10784265).

This article is part of the following sections: