Pyomyositis in an Immunocompetent Intravenous Drug User

Introduction:

Infectious myositis is classically defined as a purulent infection of skeletal muscle and is seen in patients residing in tropical climates or in patients with immunosuppression [1]. In rare cases it has been seen in immunocompetent patients with a history of trauma or injection drug use[6]. Diagnosis is challenging and is often made based on imaging, with physical exams being highly variable and laboratory analysis being non-specific [1].

The diagnostic challenges posed by infectious myositis are owed to its clinical course. It begins with mild and nonspecific symptoms such as pain and fever, and progresses to catastrophic systemic toxicity with septic shock and multisystem organ failure.

Early in the disease course symptoms can be non-specific and easily mistaken for other musculoskeletal complaints. Cases of misidentification of myositis as septic arthritis have been reported in children [2,3] but these authors were unable to find any similar case reports of misidentification in adults. Rapid diagnosis and administration of appropriate treatment is crucial, as patients with early pyomyositis may be managed with antibiotics alone. Later-presenting cases require surgical drainage and carry substantially increased morbidity and mortality[1].

Case:

The patient is a 31-year-old male with a history of Hepatitis C Virus infection, intravenous drug use of opiates, and prior septic arthritis of the left knee, who presented to the Emergency Department in the evening with atraumatic left knee pain. The patient recalled 3-5 days of intermittent aching in the affected knee, however the current episode of pain began approximately 12 hours prior to presentation upon awakening, and had been constant and progressively worsening throughout the day resulting in pain with ambulation. This prompted the patient’s first presentation to the ED. There was associated swelling of the superior aspect of the knee joint, and the pain worsened with movement and weight-bearing. At that time, he denied fever, chills, night sweats, or pain or swelling in other joints. His last drug injection was two hours prior to arrival. His previous septic arthritis was in June 2019, was incompletely treated, but resolved.

On initial physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were unremarkable, without fever, tachycardia, or hypotension. There was pain with passive and active range of motion of the knee joint, mild tenderness and swelling overlying the joint, and soft compartments throughout the affected extremity. The remaining physical exam was normal. Blood work demonstrated a mildly elevated C-Reactive Protein (CRP) of 1.6 mg/dL and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) of 15 mm/hr. The remaining values of the Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP) were unremarkable, with a white blood cell count of 6.8. An x-ray of the left knee showed a small suprapatellar effusion, and otherwise no acute abnormalities. At this point the Emergency Physician became concerned for septic arthritis and an arthrocentesis was performed. Synovial fluid analysis yielded an inflammatory pattern with no organisms on gram stain or culture (Appearance Cloudy, Viscosity High, WBC 5592, RBC 4607, Neutrophils 92, Leukocytes 7, absent crystals). Given the patient’s non-specific but concerning clinical picture he was admitted to the observation unit for pain control, empiric Vancomycin 1g IV and Cefepime 1g IV, and serial exams. Orthopedic surgery was also consulted. Unfortunately, 4 hours into his stay the patient elected to leave against medical advice.

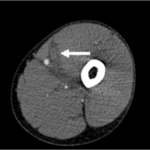

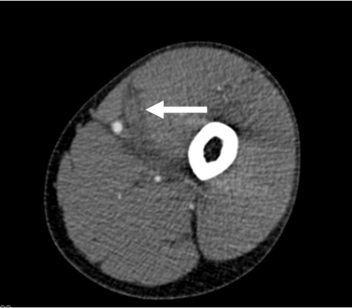

The patient returned to the Emergency Department 12 hours later with severely worsened pain now localizing to the left anterior thigh and a complaint of new-onset numbness and paresthesias of the medial portion of his left lower extremity below the knee in the saphenous nerve distribution. He was also noted to have pain with passive flexion and extension of the left knee. His left anterior thigh was tense, swollen, and erythematous. On repeat laboratory analysis, his white blood cell count had risen from 6.8 to 12.5 x103/mcL with a neutrophilic predominance, and his repeat CRP and ESR were 17.8 mg/dL and 35 mm/hr, respectively. Blood cultures were obtained however yielded no organisms, likely owing to the recent administration of antibiotics during the patient’s prior ED visit. Computed tomography (Figure 1) of the left lower extremity with contrast demonstrated infectious myositis, presumed to be bacterial in etiology, of the vastus intermedius without abscess. In the Emergency Department, he was treated with Vancomycin 1.5g IV and Piperacillin-Tazobactam 4.5g IV. An emergent consult was placed to the general surgery service, and the patient was evaluated in the ED for an emergent drainage and possible fasciotomy. Sadly, prior to surgery the patient again left against medical advice. Attempts to contact the patient for follow-up were unsuccessful as the telephone number provided by the patient was not connected to a working phone.

Figure 1. 2.2 x 5.0 x 25.0 cm poorly defined hypodense lesion within vastus intermedius muscle that does not demonstrate peripheral enhancement. Likely infectious myositis.

Discussion:

Pyomyositis is classically described as occurring in tropical regions, although cases in temperate climates are becoming increasingly more common[4]. Pyomyositis represents between approx. 2-4% of admissions to surgical services in endemic areas. This case occurred in the United States, where infections myositis is quite uncommon. In total only 98 cases of the disease were reported in the US between 1972 and 1992. Our case of a young male with no history of trauma or immunocompromise represents a rare case of IVDU associated infectious myositis in an immunocompetent adult [1]. While HIV-associated myositis has been described numerous times, this patient had a negative HIV test confirmed during their ED stay [5].

Diagnosis of pyomyositis is primarily based on radiographic findings, with MRI being the gold standard but Computed Tomography being far more accessible in the Emergency Department setting [6]. Laboratory analysis often reveals a nonspecific inflammatory pattern of leukocytosis and ESR and CRP elevations. Blood cultures are positive in between 10-35% of cases, and can be useful in identification of the causal organism [1].

Intravenous drug use has been associated with pyomyositis, where muscle tissues are hematogenous seeded from pathogens introduced into the blood from dirty needles or non-sterile injection sites. The clinical course of infectious myositis manifests in 3 distinct phases: Stage 1 is characterized by swelling, dull, achy muscular pain, and low-grade fevers. Stage 2 is further characterized by the development of edema, severe pain, and purulent material with or without discrete abscess formation. Stage 3 is characterized by progression from localized infection to systemic toxicity, with septic shock often coupled with embolization of bacteria to other organs such as the heart, lungs, and brain. This patient likely falls into the second stage, considering his exquisite pain and edema noted on CT scan. While pyomyositis is associated with Staphylococcus aureus in over 90% of culture positive cases [7], only between 10-35% of cases ever reveal positive blood cultures. In our case, the patient’s negative cultures could have been due to the patient’s prior dose of antibiotics on his initial ED visit, or related to the patient having not yet progressed to the stage of bacteremia and systemic toxicity.

Viral myositis has also been described, with commonly known culprits being influenza viruses, enteroviruses, HIV, and even Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This patient has no known recent viral illnesses, and his chronic HCV infection is more often associated with inflammatory non-infectious myopathies such as polymyositis [8,9].With negative blood and synovial fluid cultures and gram stain, and the patient leaving AMA before thorough diagnostic work up, the causative organism of this patients myositis remains unknown.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this patient represents an atypical case of pyomyositis initially masquerading as septic arthritis. While his work-up was complicated by leaving against medical advice multiple times, his ultimate diagnosis, infectious myositis, was delayed because of its initial similarity of presentation to septic arthritis. Although uncommon, it is important for physicians in the Emergency Department to be aware of infectious myositis in immunocompetent patients. As delayed diagnosis and treatment of infectious myositis is associated with poorer outcomes, the sooner it can be ruled out, the better the prognosis.

References

- Comegna L, Guidone PI, Prezioso G, et al. Pyomyositis is not only a tropical pathology: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10(1):372.

- Shuler FDB, Grant S.; Stover, Cody; Johnson, Brock; Modarresi, Milad; and Jasko, John J. Pyomyositis mistaken for septic hip arthritis in children: the role of MRI in diagnosis and management. Marshall Journal of Medicine. 2018;4(2).

- Chen WS, Wan YL. Iliacus pyomyositis mimicking septic arthritis of the hip joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1996;115(3-4):233-235.

- Chauhan S, Jain S, Varma S, Chauhan SS. Tropical pyomyositis (myositis tropicans): current perspective. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(943):267-270.

- Lam R, Lin PH, Alankar S, et al. Acute limb ischemia secondary to myositis-induced compartment syndrome in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(5):1103-1105.

- Agarwal V, Chauhan S, Gupta RK. Pyomyositis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011;21(4):975-983, x.

- Crossley M. Temperate pyomyositis in an injecting drug misuser. A difficult diagnosis in a difficult patient. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(3):299-300.

- Uruha A, Noguchi S, Hayashi YK, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in inclusion body myositis: A case-control study. Neurology. 2016;86(3):211-217.

- Crum-Cianflone NF. Bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and viral myositis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(3):473-494.

This article is part of the following sections: