Case Report: Thunderclap!

Case Presentation

A 36-year-old female presented to the emergency department for evaluation of a headache. The patient’s only medical history included anxiety and an uncomplicated childbirth three months prior.

Three hours prior to arrival, the patient was going about her daily activities when she developed a sudden onset, 10/10 headache. The headache was described as severe and radiated to the left side of her head. The patient reported associated photophobia, left sided neck pain, nausea and vomiting. She denied any trauma or history of similar headaches.

On exam, the patient appeared in distress secondary to pain, while shielding her eyes from the light and actively dry heaving. Her vital signs were remarkable for a slightly elevated blood pressure of 140/67 and bradycardia to 37 beats per minute. Her neurologic examination was benign aside from photophobia, notably without any visual field deficits, cranial nerve deficits or motor abnormalities.

Although the patient met none of the institution’s “stroke alert” criteria, given the patient’s distress and concerning symptomatology, CT imaging was expedited. The chief differential diagnosis was intracranial hemorrhage.

Introduction

The thunderclap headache is a well-known and feared presentation amongst emergency medicine clinicians. This headache is distinguished from others by both its rapidity of onset and severity in nature. While there are many intracranial causes of a thunderclap headache, pituitary apoplexy (PA) is a rare and overlooked cause for this type of headache.

Pituitary apoplexy is a potentially lethal clinical syndrome characterized by sudden hemorrhage into the pituitary gland. It is most commonly associated with pituitary adenomas. PA can also be seen when a normal pituitary gland becomes under-perfused, infarcts and bleeds (e.g. Sheehan syndrome). Pregnancy and anticoagulation use are important precipitants associated with PA. While a headache is the most common symptom, the clinical presentation of PA can vary from mild visual disturbances to severe disability, such as coma, or even sudden death. Below is a case report highlighting PA presenting with the well-known red flag feature for high-risk headaches: “thunderclap.”

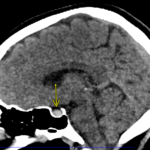

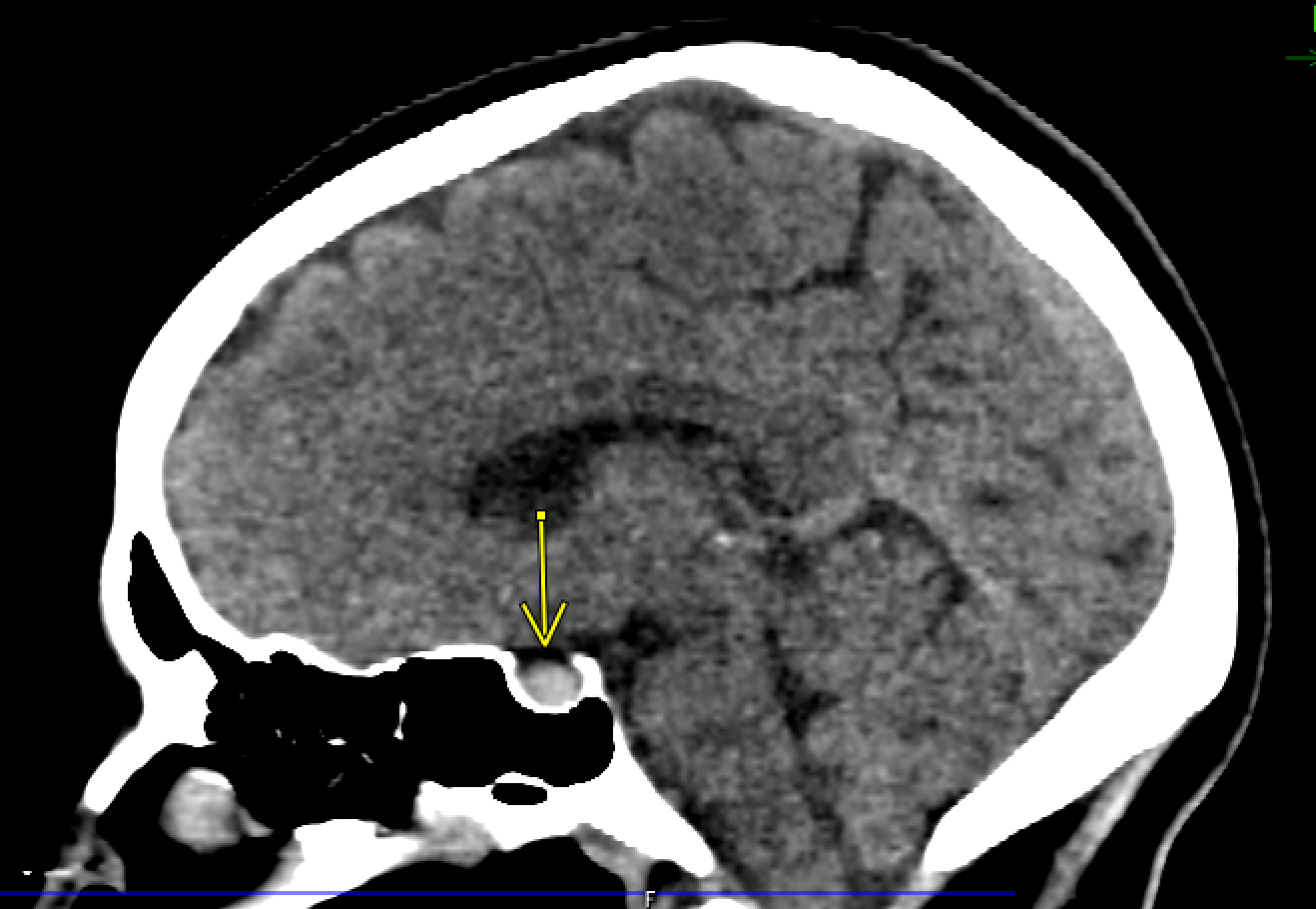

Imaging

CTA imaging of the head and neck was obtained. The reading radiologist concluded there was an 8×7 mm hyperdensity in the pituitary gland seen on the non-contrast portion of the study. This lesion was thought to represent hemorrhage within a pituitary adenoma. Otherwise, there were no other gross abnormalities, signs of midline shift, or signs of herniation.

Management/Outcome

Upon CT interpretation and correlation with clinical presentation, it was recognized that the patient required emergent neurosurgical evaluation. The patient was promptly transported from the free-standing ED where she presented to the institution’s nearby tertiary care site. There, she was rapidly evaluated by neurosurgery. Prior to transfer she was treated with normal saline, ondansetron, hydromorphone and magnesium, and the patient’s head of bed was placed at 30 degrees.

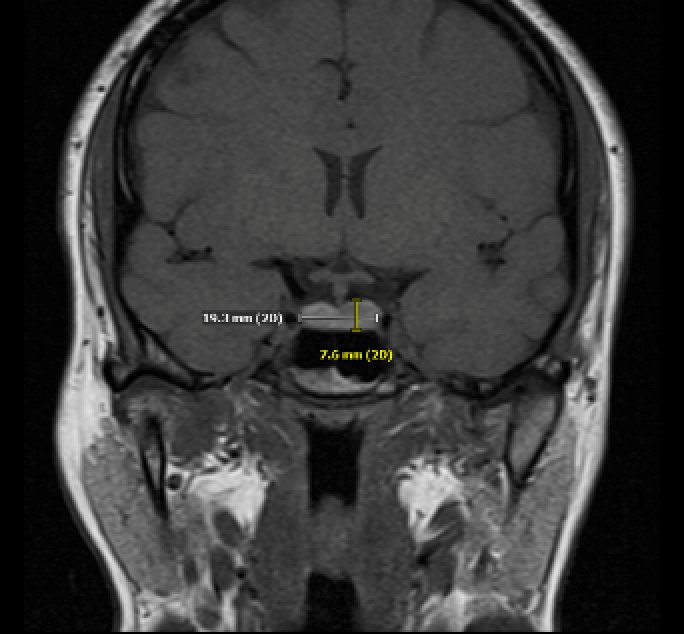

The patient underwent an MRI of the sellar region that confirmed the prior CTA results: “findings are in keeping with the clinical diagnosis of pituitary apoplexy with hemorrhage within both sides of the pituitary gland.” Diagnostic testing and treatment included a pituitary panel, serum cortisol, ACTH, estradiol, IGF1, prolactin, TSH, free T4 followed by administration of hydrocortisone 100 mg IV.

The patient was promptly admitted to the neurologic intensive care unit and remained clinically stable in the ICU for two days. Her headache improved with analgesic medications. The patient was deemed not a surgical candidate by neurosurgery, was evaluated by endocrinology inpatient, and was discharged home with a steroid taper and close outpatient follow up.

Conclusion

The thunderclap headache remains one of the most feared complaints for any patient presenting to the ED, as it is commonly considered in association with intracranial aneurysms. PA is a clinical syndrome that ED providers should consider when patients presenting to the ED report a thunderclap headache. Despite its rare occurrence with community-based studies finding a prevalence of 6.2 cases per 100,000 individuals and broad presenting symptomology ranging from a mild headache to sudden death, an emergency physician needs to be able to promptly recognize these patients as this represents a surgical emergency.

CT imaging is a limited modality in the diagnosis of PA. As with diagnosing subarachnoid hemorrhage, the ability to detect hemorrhage in the pituitary gland decreases with time as the blood density decreases. CT has been found to be diagnostic in only 21-28% of PA cases, while an intrasellar mass is visualized in 80% of PA cases. If CT imaging identifies an intrasellar mass without hemorrhage in a case with clinical concern for PA, the patient requires an emergent MRI as it is the superior diagnostic modality. MRI has been found to confirm the diagnosis in 90% of patients.

Once diagnosed, PA can be managed surgically or medically. Both neurosurgical and endocrine consultation are required to make this determination. Surgical management consists of resecting the hemorrhagic region with a goal of resolution of symptoms. A strictly medical approach is an option in cases with absent or mild stable neuro-ophthalmic signs. These patients can present with elevated blood pressure which should be treated like other types of intracranial hemorrhage with antihypertensives. In our patient’s case, it was noted that the hemorrhage shrunk on outpatient MRI approximately three weeks later. Since endocrine dysfunction is a common complication, patients with PA should be evaluated for the need for corticosteroid and other hormonal replacement based on symptomatology and lab findings prior to discharge. Specifically, these patients can develop marked hypotension with development of cortisol deficiency which should be treated with intravenous fluid, corticosteroid therapy and pressors to combat hypoperfusion. ■

References

- Briet C, Salenave S, Bonneville JF, et al. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocr Rev 2015;36(6):622–645. doi:10.1210/er.2015-1042. [PubMed]

- Diri H, Karaca Z, Tanriverdi F, et al. Sheehan’s syndrome: new insights into an old disease. Endocrine 2016;51(1):22–31. doi:10.1007/s12020-015-0726-3.

- Fernandez A, Karavitaki N, Wass JA. Prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a community-based, cross-sectional study in Banbury (Oxfordshire, UK). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72(3):377–382. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03667.x.

- Ishii M. Endocrine Emergencies With Neurologic Manifestations. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2017;23(3, Neurology of Systemic Disease):778-801. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000467

- Raappana A, Koivukangas J, Ebeling T, Pirila¨ T. Incidence of pituitary adenomas in Northern Finland in 1992-2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95(9):4268–4275. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0537.

- Rajasekaran S, Vanderpump M, Baldeweg S, et al. UK guidelines for the management of pituitary apoplexy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;74(1):9–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03913.x.

- Semple PL, Jane JA, Lopes MB, Laws ER. Pituitary apoplexy: correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological results. J Neurosurg 2008;108(5);909–915. doi:10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/0909.

- Singh TD, Valizadeh N, Meyer FB, et al. Management and outcomes of pituitary apoplexy. J Neurosurg 2015;122(6):1450–1457. doi:10.3171/2014.10.JNS141204.

This article is part of the following sections: