Hematologic Emergency: Delayed Hyper-hemolytic Transfusion Reaction in a Pediatric Sickle Cell Patient

Background

Individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) often receive blood transfusion for acute on chronic anemia due to vaso-occlusive crisis, splenic sequestration, acute chest syndrome and many other reasons. Alloimmunization is one of the many risks of blood transfusion in individuals with sickle cell disease that can lead to delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction (DHTR). Cases with hyperhemolysis are rare but life-threatening. Patients may present up to three weeks post transfusion with symptoms of pain, worsening fatigue, fever, and hematuria. The mainstay of treatment includes intravenous immunoglobulin, glucocorticoids, and phenotypically matched PRBCS.

Case Description

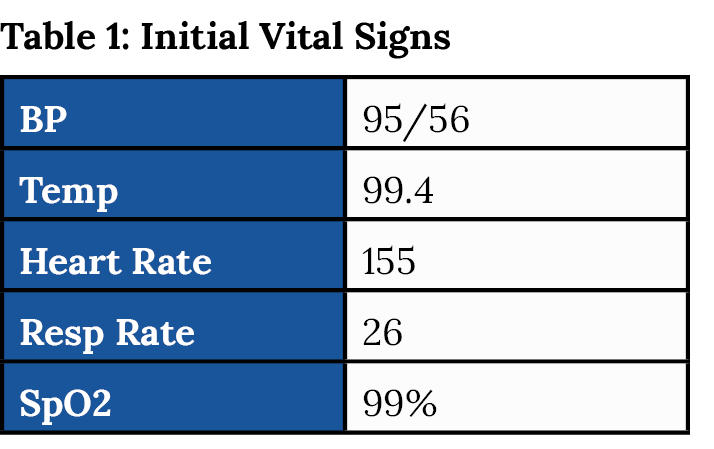

The patient is a 6-year-old female with a history of sickle cell anemia, Hgb SS, who presents to the emergency department with a complaint of hematuria and lower abdominal pain that started three days prior to her arrival. She has never had noticeable blood in her urine, and her father states that her symptoms are different from her usual sickle cell pain crisis. There were no reports of chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, headaches, vision changes, nausea or vomiting. Upon further questioning, the patient’s father revealed that they recently returned from Senegal, Africa, where they were vacationing for two months. While there, she had a vasocclusive crisis requiring blood transfusion. The transfusion was three weeks prior to this visit.

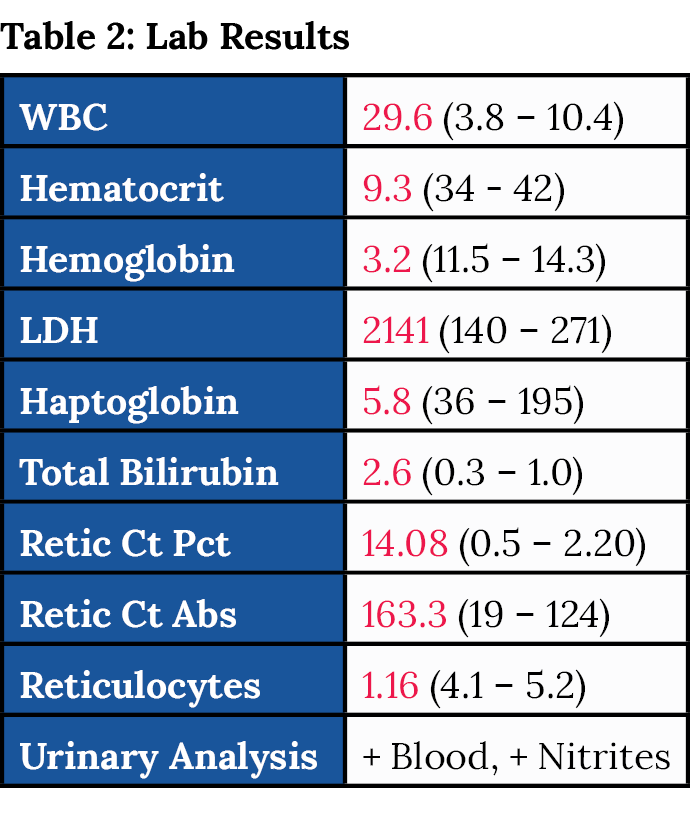

On admission she was given methylprednisolone and IVIG to inhibit destruction of RBCs. The patient became hypoxic and increasingly tachycardic shortly after admission. Repeat hemoglobin was 2.8. The patient was intubated to help decrease metabolic demand and then upgraded to the PICU.

The patient had a complicated hospital course. Blood transfusion was continued until the goal of greater than 8 was achieved. She was continued on IVIG and methylyprednisolone. She was extubated after three days. The patient later developed seizures and was found to have an acute CVA. After 11 days, she was discharged home in stable condition with no neurological deficits.

Discussion

This is a 6-year-old female with history of sickle cell disease who presented to the emergency room with abdominal pain and hematuria. This case highlights the importance of a quick and detailed history (including recent travel) to hone in on the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis narrowed to include delayed transfusion reaction once it became known that she had a recent travel history to Senegal where she received blood transfusion.

In certain parts of the world outside of the U.S., the blood cross matching process may not be as stringent, and she likely did not receive phenotypically matched blood which may have triggered her hyper-hemolytic transfusion reaction.

Hemolytic transfusion reactions (HTRs) occur when there is immunologic incompatibility between a transfusion recipient and the red blood cells from the blood donor. HTRs can range in severity from asymptomatic to severe causing DIC and shock. HTRs can be acute, occurring during the transfusion or within 24 hours after the transfusion. Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction (DHTR) typically occurs 1-2 weeks post transfusion but can be up to three weeks. Many cases of DHTRs are mild, but it can be severe when there is hemolysis.

In this case, the patient had a DHTR as she presented three weeks after transfusion. Patients with DHTR typically have extravascular hemolysis, which is hemolysis that occurs in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Her history of sickle cell disease puts her at risk for intravascular hyper-hemolysis in which transfused red blood cells is accompanied by hemolysis of the patient’s own red blood cells. This phenomenon has been seen most often in patients with SCD who have received multiple transfusions. Lab workup in these patients will show elevated LDH and indirect bilirubin with decreased haptoglobin levels. The hemoglobin level may be lower than expected given the patient’s clinical picture. In this case, the hematologist had asked to repeat H&H as her clinical picture initially on presentation did not fit a HgB of 3.2.

The mainstay of treatment in these patients is with glucocorticoids and intravenous immunoglobulin. If no improvement, patients may benefit from plasmapheresis.

In this case, the patient was transfused immediately with phenotypically matched PRBC, started on IVIG and methylprednisolone. She went into shock and was intubated to decrease metabolic demand and slow the hyper-hemolysis process. Her condition improved after intubation and she did not require plasmapheresis or addition of DMARDs to treatment regimen.

Conclusion

Delayed hyper-hemolysis reaction is a rare complication of blood transfusion in sickle cell patients. This is a hematologic emergency requiring immediate resuscitation, including phenotypically matched PRBCs and intensive care unit admission. Making the diagnosis promptly is challenging as these patients can present up to three weeks post blood transfusion with wide ranging symptoms. This case highlights the importance of a detailed history to make prompt diagnosis and facilitate early treatment. ■

References:

- DeBaun M, Chou S. Transfusion in sickle cell disease: Management of complications including iron overload. UpToDate. Accessed September 1, 2022.

- Tobian A. Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions. UpToDate. Accessed September 1, 2022.