Trends in Exposures to the Florida Poison Control Centers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

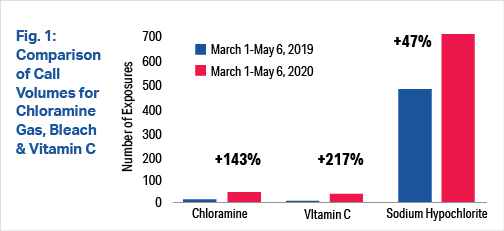

The novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 has caused notable trends in exposure calls to Florida’s Poison Control Centers (FPCC). Call trends were reviewed from March 1-May 6, 2020 and compared to the same timeframe for the previous year using data from the National Poison Data System. The exposure trends were examined to see if there were notable differences in call trends that may be of potential public health significance and necessitate awareness.

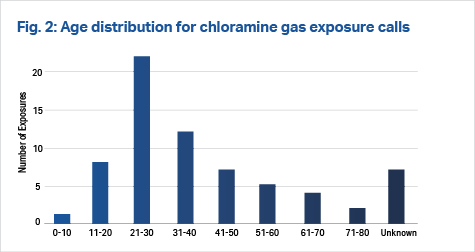

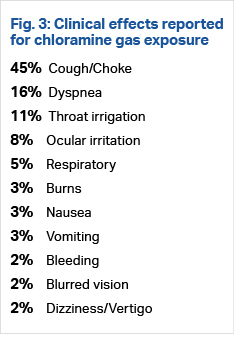

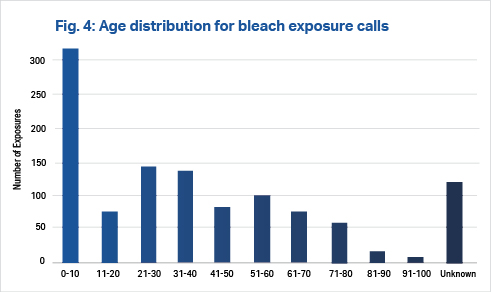

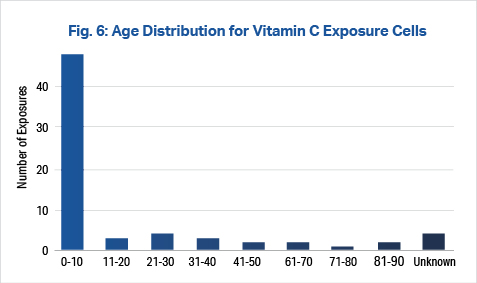

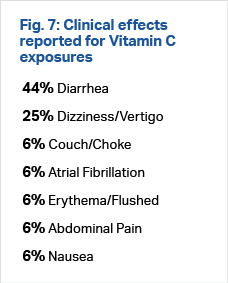

Substantial increases in exposures were seen in reference to calls for bleach products (47%), chloramine gas (143%) and vitamin C (217%) (Fig. 1). Chloramine gas exposures were more frequent in younger adults in the 21-30 age range, while vitamin C and bleach exposures occurred predominantly in younger patients, most under the age of 10 (Figs. 2, 4, 6). The most common clinical effect reported by callers exposed to chloramine gas was cough/choke (45%).

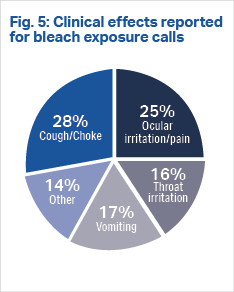

There were multiple clinical effects reported by callers exposed to bleach, the top five reported being: cough/choke, ocular irritation/pain, vomiting, throat irritation and other. A large proportion of callers exposed to vitamin C experienced diarrhea and dizziness/vertigo (Figs. 3, 5, 7). The majority of medical outcomes associated with the three substances were not followed due to minimal clinical effects expected. The sole major effect seen with ingestion of bleach was atrial fibrillation and flutter. Vitamin C had one moderate effect, which was atrial fibrillation and flutter. It is unclear if these were isolated findings or were directly related to toxic ingestions of bleach and vitamin C.

Factors causing the increase in exposures most likely stem from fear surrounding adequate disinfection and prophylactic measures to protect against the novel coronavirus. News and social media may also be lending to the increase in contact with these substances. Examples of questions asked to the FPCC were concerning, ranging from “if boiling bleach will disinfect the air” to “which disinfectants are safe to inject.” Although, thankfully, most of the exposures to the FPCC had minimal clinical effects, these exposures have the potential of becoming a serious public health issue. There are many toxic effects associated with all three of these substances, some of which have been shown to be fatal. It is important for the public to be informed about the effects related to these substances. The substantial increase in exposures to vitamin C is concerning, especially in young children. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, clinicians may benefit from awareness of some of these substances and their toxic effects.

Chloramine gases are produced when household bleach and ammonia containing products are mixed together. When chloramine gas is inhaled, it releases ammonia, hydrochloric acid and oxygen free radicals upon contact with mucous membranes. This subsequently causes irritation to the epithelial lining of the upper and lower airways. Low concentrations of the gas produce mild symptoms, while higher amounts lead to corrosive symptoms such as pneumonitis and edema. The most common symptoms reported are coughing and shortness of breath, with resolution of symptoms within one to six hours. Severe symptoms reported are skin burns, ocular injury and multi-organ dysfunction. Although there are multiple news reports of severe accidental exposure and suicide using chloramine gas, there is a single case report resulting in fatality due to exposure to chloramine gas, most likely from asphyxiation. [1-6]

Bleach, or sodium hypochlorite, is a caustic that is commonly found in household cleaning products. The concentration of bleach differs depending on the product. However, most household products such as Clorox® contain 5.25% sodium hypochlorite. Therapeutic uses for diluted sodium hypochlorite solutions are to irrigate skin wounds and dissolve necrotic tissue such as Dakin’s Solution, which is 0.4-0.5% sodium hypochlorite. Diluted bleach solutions are also used in root canal irrigation. Toxicity arises from its caustic effects as an oxidizer when in contact with mucous membranes.

Most exposures of household bleach have mild effects. Ingestions of large quantities of household bleach or any ingestion of industrial strength bleach (20% hypochlorite) can cause ulceration and perforation of the esophagus, along with hypotension, hyponatremia and hyperchloremia. Severe cases can result in dyspnea, stridor, pulmonary edema, cyanosis and pneumonitis, especially in those with preexisting asthma and COPD. Ocular exposure can result in conjunctival and corneal injury. Parenteral exposure has been shown to cause intravascular hemolysis and multiple end organ damage. A case report of IV exposure to sodium hypochlorite was reported when a patient received 150 mL of 1% sodium hypochlorite. The patient subsequently developed bradycardia, hypotension and tachypnea. The patient improved with symptomatic treatment. [7-10]

Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, is a water-soluble vitamin. Most of the water-soluble vitamins do not cause significant toxic symptoms. The maximum safe dose of vitamin C to be prescribed is 1 gram. Multiple therapeutic and prophylactic uses have been studied for vitamin C. However, there has not been concrete evidence to support disease prevention. A few studies have shown vitamin C deficiency may be related to increased risk of influenza infections, though this has not been proven. There are current trials studying the effect of vitamin C on the COVID-19. However, other studies have shown adverse effects from chronic and large ingestions of vitamin C. Chronic ingestions as well as administration of an acute IV dose have been linked to renal failure. Acute hemolysis has also been known to occur in children with G6PD. Studies have shown that vitamin C intake was associated with higher risk of kidney stones in men. Reports have shown that high doses of vitamin C ingestion can interfere with laboratory values such as creatinine, sodium, lactate, ammonia, total cholesterol and triglycerides. [11-14] ■

References

- Sullivan, John B., & Gary R. Krieger, editors. Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures. 2nd ed, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

- Goldfrank, Lewis R., editor. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 7th ed., McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division, 2002., p. 1457

- Tanen, David A., et al. “Severe Lung Injury after Exposure to Chloramine Gas from Household Cleaners.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, no. 11, Sept. 1999, pp. 848–49. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1056/NEJM199909093411115.

- Mrvos, Rita, et al. “Home Exposures to Chlorine/Chloramine Gas: Review of 216 Cases.” Southern Medical Journal, vol. 86, no. 6, June 1993, pp. 654–57.

- Hypochlorites and related agents. Micromedex Solutions. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Available at: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- Cohle, Stephen D., et al. “Unexpected Death Due to Chloramine Toxicity in a Woman with a Brain Tumor.” Forensic Science International, vol. 124, no. 2–3, Dec. 2001, pp. 137–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00592-8.

- Chlorine Bleach. https://chlorine.americanchemistry.com/Chlorine/BleachFAQs. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- Levine, Jeffrey M. “Dakin’s Solution: Past, Present, and Future.” Advances in Skin & Wound Care, vol. 26, no. 9, Sept. 2013, pp. 410–414. journals.lww.com, doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000432051.59348.cd.

- Racioppi, F., et al. “Household Bleaches Based on Sodium Hypochlorite: Review of Acute Toxicology and Poison Control Center Experience.” Food and Chemical Toxicology, vol. 32, no. 9, Jan. 1994, pp. 845–61. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/0278-6915(94)90162-7.

- Marroni, Massimo, and Francesco Menichetti. “Accidental Intravenous Infusion of Sodium Hypochlorite.” DICP, vol. 25, no. 9, Sept. 1991, pp. 1008–09. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/106002809102500919.

- Vitamin C Infusion for the Treatment of Severe 2019-NCoV Infected Pneumonia – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.Gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04264533. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- Vitamins – multiple. Micromedex Solutions. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Available at: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- Pm, Ferraro, et al. “Total, Dietary, and Supplemental Vitamin C Intake and Risk of Incident Kidney Stones.” American Journal of Kidney Diseases : The Official Journal of the National Kidney Foundation, Mar. 2016, doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.005.

- Meng, Qing H., et al. “Interference of Ascorbic Acid with Chemical Analytes.” Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, vol. 42, no. 6, Nov. 2005, pp. 475–77. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1258/000456305774538274.

This article is part of the following sections:

Samantha manages fcep.org and publishes all content. Some articles may not be written by her. If you have questions about authorship or find an error, please email her directly.